In many classrooms, students who perform well on tests forget most of what they learned just weeks later. This shows the need for instructional methods grounded in scientific research – known as Evidence-Based Practices (EBPs) – which aim to improve educational outcomes by enhancing student engagement, retention, and overall academic performance. Research examining the effects of frequent testing on Thai vocational students for instance found that those who underwent regular assessments demonstrated notably higher retention scores compared to those who did not. This suggests that without consistent reinforcement, students may struggle to retain key concepts, long-term learning that is, even if they initially perform well on assessments.

This evidence shows the importance of implementing teaching strategies that promote long-term retention, such as retrieval practice and spaced repetition. By focusing on these methods, educators can enhance students’ ability to retain and apply knowledge effectively over time.

This mismatch between performance and understanding also shows a deeper issue: Are current teaching methods built for long-term learning?

Recent insights from cognitive science offer a different approach. Durable learning stems not from how much content is covered, but from how it’s taught. Strategies like retrieval practice, metacognition, and timely feedback are increasingly proving more effective than rote memorization. Here’s how schools around the world are turning this research into real results.

Evidence-Based Learning and Long-Term Learning

The difference between evidence-based learning and long-term learning lies in their scope and focus. Evidence-Based Practices (EBPs) are instructional methods grounded in rigorous scientific research, shown to enhance student engagement, retention, and achievement. A prominent example is active learning, which fosters deeper understanding and critical thinking through collaborative and participatory experiences.

Evidence-based learning is a method; long-term learning is the outcome. Using evidence-based strategies increases the likelihood of achieving long-term learning, but the two are not interchangeable. Not all long-term learning arises from rigorously tested methods – personal interest or immersion can also result in deep retention. Likewise, evidence-based strategies may not yield durable learning if implemented inconsistently or without fidelity.

Despite the overall effectiveness of EBPs demonstrated in meta-analyses, challenges remain in their implementation. Critics point out potential biases in educational research that may overstate the benefits of newer instructional models over established ones (see, for example, debates on the use of laptops in classrooms). Moreover, contextual factors – such as classroom dynamics, student diversity, and institutional constraints – can significantly influence outcomes, indicating that a one-size-fits-all approach is unlikely to succeed.

Let’s check both into more detail:

Evidence-Based Learning

A teaching approach that draws on scientific research and empirical data to inform instructional strategies, materials, and assessment methods.

Key Features:

- Rooted in findings from cognitive science, neuroscience, and education research.

- Examples include retrieval practice, spaced repetition, formative assessment, and metacognitive reflection.

- Goal: Improve teaching efficacy based on what has been proven to work in studies.

Example:

Using low-stakes quizzes to reinforce memory because research (e.g., Roediger & Karpicke, 2006) shows testing improves recall more than rereading.

Long-Term Learning

The outcome or goal of education where knowledge, skills, and understanding are retained and can be applied well beyond the immediate learning context or exam.

Key Features:

- Focuses on durability, transfer, and applicability of knowledge.

- Can be achieved through a range of methods—not all evidence-based (though the most effective usually are).

- Sometimes compromised by cramming or surface-level memorization.

Example:

A student who learns how to analyze a historical argument in school and successfully applies that reasoning in university or civic debate years later.

5 Keys to Long-Term Learning Success

1. Cognitive Engagement Begins With Challenge

High-impact classrooms challenge students with tasks that require sustained effort and reflection – not passive listening. Research indicates that active learning strategies, which involve students in interactive tasks and discussions, lead to better educational outcomes compared to traditional lectures. At Eltham High School, for example, teachers integrate metacognitive checklists and reflective learning journals. These “desirable difficulties” encourage students to think deeply, make mistakes, and improve.

Such cognitively demanding tasks have been shown to produce stronger long-term retention, especially when paired with retrieval-based activities and spaced learning structures.

2. Metacognition as a Daily Practice

Helping students think about how they learn is a proven method for boosting outcomes. OECD research shows that learners who actively monitor their strategies outperform peers on problem-solving tasks—even when working with the same lesson content.

Practical tools like learning logs, guided reflections, and self-questioning prompts help students identify knowledge gaps early and adjust strategies in real time. Embedding metacognitive practices into everyday instruction cultivates resilience and independence.

3. Formative Feedback: A Continuous Loop

Unlike summative assessments, formative feedback in Welsh Schools offers real-time, actionable insight. Wales’ national strategy promotes “next step” feedback through mini whiteboards, low-stakes quizzes, and guided peer commentary.

This shift empowers students to respond and improve during the learning process. The OECD Schools+ Network feedback models note that feedback has the strongest effect when it is timely, specific, and focused on actionable improvements—especially when embedded in retrieval tasks.

4. Adaptive Technology as a Learning Ally

Tools like MATHia, Knewton Alta, and Khan Academy’s AI tutor Khanmigo personalize instruction using real-time student data. In Finland, schools use adaptive technology in Finnish classrooms to support diverse learning needs without increasing teacher workload.

When aligned with evidence-based methods like interleaving and spaced repetition, adaptive technology becomes a powerful tool for equity and engagement—especially in large or mixed-ability classrooms.

5. The Right Practice, at the Right Moment

The OECD’s flagship framework, Unlocking High-Quality Teaching, synthesizes 20 proven teaching strategies across five goals: cognitive engagement, content mastery, emotional support, interactive classrooms, and formative cycles.

Notably, the framework includes practices – highlighted also in this excellent article “Teaching Smarter with Learning Science” by Bryan Goodwin in ASCD’s Educational Leadership – such as interleaving and spaced retrieval.

Want students to remember what they learn? The science is clear: Our brains retain what matters. @bryanrgoodwin explains how to use principles of cognitive science to make learning both engaging and enduring. https://t.co/KFWoB4bnvZ pic.twitter.com/12mVK7VLo3

— ISTE (@ISTEofficial) May 4, 2025

Although approaches like retrieval practice and spaced repetition may seem less intuitive, extensive research has consistently demonstrated their superiority in enhancing long-term retention compared to traditional study methods.

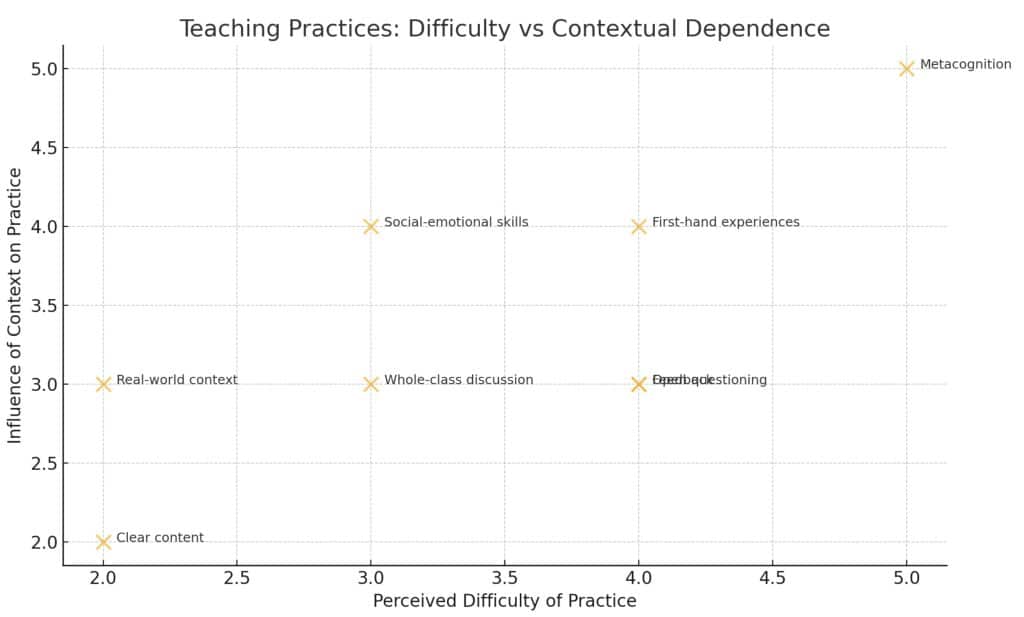

Difficulty and Context Sensitivity of Teaching Practices (Table created by WINSS)

The chart above illustrates how effective practices vary in difficulty and context sensitivity, guiding educators to balance ambition with local realities.

How does Evidence-Based Learning Align with SDGs?

The push for evidence-based learning strategies is not only a matter of educational effectiveness – it is also a key contributor to several sustainable global development goals. By integrating cognitive science into classroom practice, schools are advancing equity, innovation, and global collaboration in education. This section outlines how the teaching approaches discussed above directly support the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), especially those tied to quality education, reduced inequalities, and inclusive innovation.

| Goal | Relevance to Article |

|---|---|

| SDG 4 – Quality Education | Promotes inclusive and evidence-based teaching strategies. |

| SDG 10 – Reduced Inequalities | Helps close learning gaps through adaptive and differentiated approaches. |

| SDG 9 – Innovation and Infrastructure | Encourages the use of adaptive technology to enhance education delivery. |

| SDG 17 – Partnerships for the Goals | Based on collaborative efforts such as the OECD Schools+ Network. |

Need to go Beyond Surface-Level Performance

The science of learning is clear: students retain more, understand deeper, and apply knowledge better when instruction moves beyond surface-level performance. As explored throughout this article – and echoed in ASCD’s teaching science research – core strategies such as retrieval practice, spaced repetition, formative feedback, and metacognition are central to building long-term learning.

Our review of international practices shows how schools are integrating these principles in diverse ways – from formative feedback in Welsh schools to adaptive technology in Finnish classrooms and Eltham High School. Each approach reinforces a shared shift: away from passive review and toward active, deliberate engagement.

Moreover, the Unlocking High-Quality Teaching framework offers educators a structure to implement these methods with sensitivity to context and classroom diversity. Whether through challenge-based tasks or adaptive scaffolding, the goal remains the same—ensuring that learning endures beyond the test.

The focus on evidence-based teaching practices can help educators to let students become not just better performers, but better thinkers. Understanding the nuances of these strategies – including their benefits, limitations, and implementation challenges – remains crucial for educators, policymakers, and researchers alike.