Over the past decade schools have increasingly adopted laptops, tablets, and other digital devices as standard tools of instruction. Governments promoted their use under the assumption that technology enhances access, engagement, and ultimately, learning. However, a growing body of research raises concerns about whether digital tools – particularly laptops – might unintentionally impair student performance when used during lessons. As a result, books returns.

As of 2025, several countries and educational institutions are scaling back the use of laptops, tablets, and other digital devices in classrooms. This shift is driven by concerns over student well-being, attention spans, and academic performance.

- Spain (Madrid): The regional government of Madrid plans to limit computer and tablet use in primary schools to a maximum of two hours per week starting in September 2025. Teachers will also be prohibited from assigning homework that requires screen use. For infant and primary students, individual work with digital devices will not be permitted, and outside-of-school screen use will be restricted.

- Sweden: Sweden is shifting its education approach by prioritizing printed books, handwriting, and quiet reading over digital devices, such as tablets, which were previously introduced in early education. This move is in response to concerns from politicians and experts about the decline in basic skills among students due to the overuse of technology. The Swedish government plans to invest significantly in book purchases and revert to traditional learning methods for children under six.

- Denmark: Denmark’s education minister announced in February 2025 that the government would push through a law banning smartphones and tablets in schools, both in lessons and during break times.

In this article we will give you some key research findings to explore how laptops influence educational outcomes, and whether this trend contradicts the goals of digitalisation.

Distraction by Design: How Laptops Influence Cognitive Focus

Digital devices provide rapid access to content, tools, and collaborative platforms. Yet, they also open the door to multitasking and off-task behaviour.

One of the most cited studies on this issue is the randomised controlled trial conducted at the United States Military Academy by Carter, Greenberg, and Walker (2017). Their research revealed that students in classrooms with laptop access scored significantly lower on final exams – by approximately 0.2 standard deviations – compared to those who used only paper and pen.

A similar study by Sana, Weston, and Cepeda (2013) found that even students seated near laptop users suffered. Their comprehension test scores dropped by 17%, suggesting that the distractions caused by visible screen activity extend beyond the individual user.

These studies are summarised below:

Summary of Laptop Use Studies and Findings

| Study | Sample Size | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|

| Carter et al. (2017) | 726 students (USA) | Laptop use reduced exam scores by ~0.2 SD |

| Mueller & Oppenheimer (2014) | 327 students (USA) | Handwritten notes led to better conceptual recall |

| Sana et al. (2013) | 38 students (Canada) | Laptop users and nearby students scored ~17% lower |

| OECD PISA (2015) | 510,000+ students (70+ countries) | Frequent school computer users performed worse in reading and math |

Why Typing Notes May Hinder Deep Learning

The mechanism behind this performance gap was explored by Mueller and Oppenheimer (2014), who compared handwritten versus laptop-based note-taking. Their research, published in Psychological Science, showed that students who wrote notes by hand retained information more deeply and performed better on conceptual questions. This was attributed to the fact that writing by hand requires summarising and processing content – whereas typing encourages verbatim transcription.

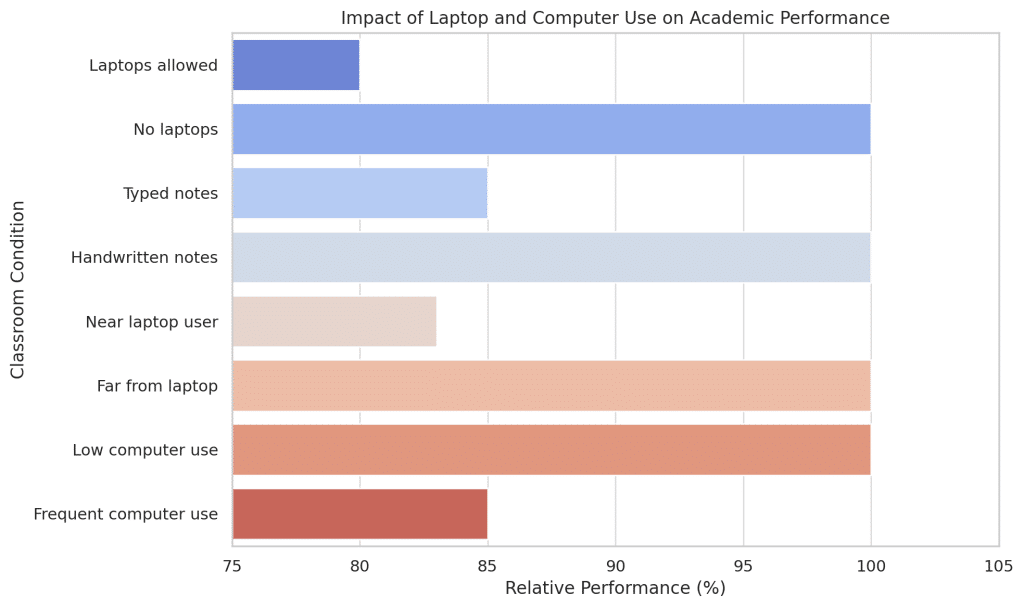

These patterns are reflected in relative performance measures visualised below:

Comparison of student performance under different classroom conditions.

Source: Carter et al. (2017), Mueller & Oppenheimer (2014), Sana et al. (2013), OECD (2015).

Large-Scale Trends: Insights from OECD PISA Dat

At a broader level, data from the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) supports the conclusion that more is not always better when it comes to computers in schools. The 2015 OECD report Students, Computers and Learning: Making the Connection stated:

“Students who use computers moderately at school tend to have somewhat better learning outcomes than students who use computers rarely… But students who use computers very frequently at school do a lot worse in most learning outcomes, even after accounting for social background and demographics.”

The implication is that balanced use may support learning, while overexposure may degrade it.

Does This Contradict Digitalisation?

The findings described above challenge assumptions about the benefits of digitalisation, but they do not inherently contradict digitalisation goals. Rather, they point to a misalignment between quantity and quality of digital use.

Digitalisation in education is intended to enhance access, equity, personalisation, and future-readiness. These goals remain valid. However, for digitalisation to support – not hinder – learning, implementation must be intentional. For example:

- Digital platforms that offer adaptive feedback can personalise instruction effectively.

- Tools like virtual science labs or collaborative wikis can extend learning opportunities beyond traditional formats.

- Structured digital note-taking (e.g., via guided templates) may mitigate shallow processing.

AI and the Future of Digital Learning

Insights from the 2020 article Artificial Intelligence in Education and Schools by Göçen and Aydemir reinforce these concerns. While AI and smart systems can support personalisation and reduce teacher workload, participants – including teachers and lawyers – warned that if applied uncritically, such tools could lead to mechanical learning and erode human connection.

Thus, the challenge is to align digitalisation with pedagogy, not to reject it outright.

Rethinking Integration Strategies

The evidence is clear: laptops and digital tools can distract, diminish deep learning, and lower academic outcomes – if used without clear pedagogical purpose. Yet, this does not mean schools should abandon digitalisation. Instead, it signals the need for smarter integration:

- Limit device use during lectures or notetaking unless pedagogically justified.

- Invest in teacher training to guide appropriate tech use.

- Prioritise digital tools that promote engagement, differentiation, or access – not mere convenience.

Digitalisation remains a powerful force in education. The challenge now is not whether to go digital, but how to go digital with purpose.